There are three areas for thinking about building independence: chances, chores, and choices.

Give them as many chances as you can to try doing things for themselves. Think about chores they can do – taking on responsibilities builds their sense of being competent, capable and important contributors to the family. Then let’s practice independent decision making by allowing them to make more of their own choices.

Chances to “Do it Myself”

Increase Accessibility

To build independence, think about how to make tasks more accessible for them. If you want them to get themselves dressed, choose clothes and shoes that are easy to get on and off. If you want them to help with cleaning, keep some cleaning supplies in their reach and store toys in containers they can open and close. If you’re nursing a baby, have a water bottle and snacks where your older child can reach them so they can help themselves if needed.

Teach Skills

Take the time to intentionally teach and practice skills, like putting on a coat or gloves or opening a cheese stick. For the first ten times, it takes a long time and is frustrating, but then your child will know how to do it themselves. Think how much time you save in the long run! (For lots of these things, search online for “hacks” for how to teach.)

Create Systems

Create systems that they can understand. Like having one container for all the toy animals and one for all the toy cars, with picture labels on them to help them remember. Or having a library basket so if they find a library book anywhere else in the house, they always know where to return it to – and when they want a book, they always know where to find one! Or writing a visual schedule of the bedtime routine with four pictures showing the four steps.

Accept the Mess

When your children “help out,” it takes longer, and it’s messy and it’s inconvenient. It’s hard to be patient, and easier to do it yourself. But, if we want to raise independent children, we have to give them chances at independence, and accept the imperfections of the learning process.

Chores – Responsibility and Teamwork

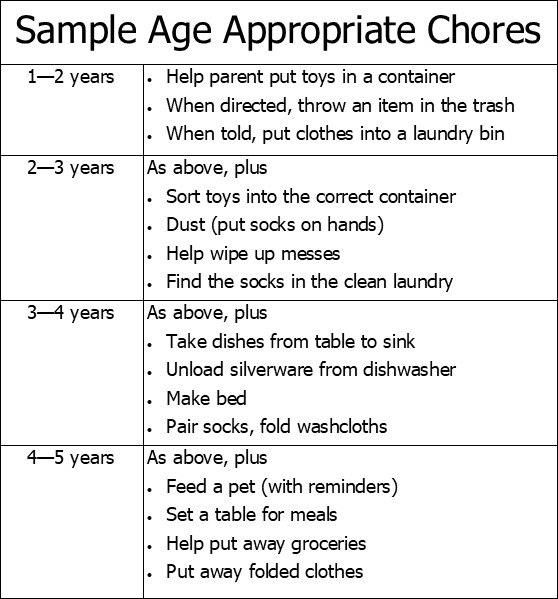

If you have a very young child, you may have never even considered chores. You may not have viewed them as being capable of contributing. But even a one year old can help with household tasks: “can you put this sock in the laundry bin?”, “can you carry this for me?”, “put the toys in the basket.” Children love to help out – doing tasks helps them feel competent and important.

Search online for “age appropriate chores” and you’ll find several charts with suggestions. Or ask other parents for ideas of tasks that you could try having your child help out with. For example, a 2 year old could help wipe up messes, a 5 year old could match socks, and a 7 year old could water plants – though you’ll need to have a system to help them remember.

Your child will not be as good at doing things as you are…. If your three year old makes the bed, it’s not going to have perfect corners! If they feed the dog, they may spill kibbles on the floor. Your 5 year old won’t load the dishwasher perfectly – but they can at least put a cup and spoon in there that you can finesse later. Experiment with options, trying several out to see where they can be successful and which chores make sense to assign on a long term basis.

You can ask your child for input on what jobs they would LIKE to do or what would help motivate them. A kid who hates folding laundry might be more willing to do it if you watch movies together as you fold. A kid who likes feeling strong might like the heavy work – carrying baskets of laundry, putting out the trash, shoveling snow, bringing the groceries in from the car… Some teenagers might prefer doing the grocery shopping to cleaning the house.

Chores: The Teamwork Approach

Often chores are approached in an if/then punitive way where the parent is in control: “If you don’t put your laundry away then you can’t play your game.” This often leads to battles of wills.

The teamwork approach is: “What do WE need to do so that our home life functions well for all of us? Here are things I can help with – what can you help with?” And then on chore days you can use the when/then approach “we as a family all have chores today – but when we get all our work done, then we get to celebrate a job well done by having fun together!”

Choices

As they do more things independently, they’ll make more choices. If they’re getting themselves dressed, they choose their clothes. If they’re packing lunches, they choose what food to pack. If they’re responsible for homework, they decide whether to do math or English first.

It’s important to note that the parent still defines what are acceptable options to choose from! For example: you could tell a two year old: “it’s cold today, so you need to wear a warm shirt – do you want this blue one or the red one?” Or tell a three year old: “There are three things you need to do to get ready for preschool – which one do you want to do first?” A rule of thumb is for a two year old offer two options. A three year old gets three options. An eight year old has a lot of options, with clear criteria set by you. For example, an eight year old packing their lunch might be told they have to have at least one protein, at least one fruit, and one starch. (And you’ve taught them what this means and set up systems that make it easy for them to do this.)

We can also offer choices in other areas to practice decision making. For example, they can have some “free choice” time in their daily schedule where they get to decide what they do and you’ll play along. Older children can decide what extracurriculars or camps they do.

Some parents give a young child allowance that they can choose what to spend it on. As the child gets older, they get more allowance, but it’s split into three pools: spending, saving and sharing. They can use spending money on anything anytime. They have to declare in advance something that they are saving toward and can purchase it when they have enough. And sharing money can be for gifts or for charitable donations they choose.

Sometimes children will make poor choices. If they choose not to wear a coat on a cold/wet day, it’s a learning experience! (Now, I won’t do this on a day my child is going to preschool and the teachers would have to deal with the unhappy child that results… but I would do it on a day I was just taking my child for a short trip to the park.)

It’s important to let them do so and to experience the consequences in a low stakes environment so they can learn from their mistakes and make better choices in the future.

Image credit: http://wesandrachel.blogspot.com/2010/08/tot-school-catching-up.html, marked as Creative Commons